The Rebirth of Melchior Dronte by Paul Busson and translated by Joe E Bandel

Among the otherwise light-hearted and good-natured

people were mingled at that time riffraff and tavern scavengers,

who were only interested to fill their coffers, to drink, to

fornicate, to whore, to splurge and to murder. Also even among

the leaders, many of whom meant well, they were swamped by

those who would use any means and who stirred up the

common instincts of the crowd in order to make himself

popular with the plebs. A gentleman of my standing would be

better in the safety of home, instead of traveling in a country

where there is neither discipline nor justice nor security. I

would soon see that a limited measure of freedom is like a

fortifying drink of good wine, but a mad exuberance like the

exuberance, however, as it reigns here, is like senseless

intoxication and insanity.

This kind of expression in a mail coach driver surprised

me; however, his expression and posture told me that he

belonged to the educated classes. And so I addressed the

question to him, how it comes that a man of such politesse

could not find any other position than that of a stagecoach

driver.

The coach driver smiled and said:

“Don’t bother addressing me as a gentleman! During this

time I am quite modest and observe as a philosopher that which

I cannot prevent. Who in such times holds his head too high

can easily lose it, and since I only have this one, I am worried

about it and on my guard. – Forgive me, mein Herr, but the road

is getting so bad that I must turn my attention to it.”

With these words he turned and seemed to pay attention

only to his reins and the trotting of the horses. But already the

nonchalant posture of the reins, indicating great practice and

the noble certainty of his movements told me, from which

social class my coach driver came from.

In front of a town, which we were approaching, we were

stopped by a strong group of armed peasants, who, they

claimed, had been assigned to guard the road. One of them

grabbed the reins of the horses, which were walking at a walk,

while two of them, with their muskets extended, stepped up to

the coach.

But the coach driver, about whose fine and educated

nature, I had just voiced my thoughts to, spat in a vulgar

manner into his hands and shouted in the lowest dialect of the

area:

“You dung-scratchers and filthy beetles, you lice-pack

want to dare to stop a citizen commissar? Death over my life, if

I don’t bring you under Doctor Guillotine’s machine, you

thieves and skunks! Away, by the fiery claws of the devil, or I

shall ask the citizen commissar in the coach to write your

names in his pocket-book!”

Immediately they drew back, pulled off their greasy hats

and shouted:

“Long live freedom!”

Our coach rolled on. The driver laughed to himself.

“What did you say about the machine of Doctor

Guillotine?” I asked him.

“Ah – have you heard nothing of it? Imagine that they put

you on a board between two beams. High above hangs a knife

with a slanting edge, which falls and separates the head so

neatly from the trunk as if it were only a head of cabbage on a

thin stalk. It travels around the country, the machine of Father

Guillotine.”

In my mouth was suddenly a tepid, sweetish taste, which

almost made me sick. It was the air in this country that I had in

my mouth. It tasted like blood. And with a second-long freeze I

thought of the words of Demoiselle Köckering, her shrill cry–

“A knife hangs – falls -‘”

In the city, whose gate lay before us, a bell began to ring

low and menacingly: Death-Death-Death-Death.

My fear vanished as quickly as it had come.

“Non omnis moriar,” I said to myself.

“I will not die completely!”

I was standing under the archway of the Paris house

where I lived and looked down the street.

Muffled sounds came closer. Whistles, shrill laughter.

A bunch of soldiers in various uniforms, red and white

striped, dirty trousers on their legs, crushed hats with the new

cockades on the long hair, came down the street with

shouldered rifles. Two barefoot ragamuffin boys ran forward as

drummers. On one of the two drums I recognized the scratched,

colorful coat of arms of the Esterhäzy regiment.

Behind the soldiers ran a large crowd of people, girls,

men, women and children. Among the people one saw ragged

prostitutes, fellows with murderous clubs, tramps, and lowly

rabble. In the middle of this throng swayed and bumped a high-

wheeled cart on which six people were sitting. The first one my

eyes fell on–

Merciful God!

The cart stopped because the procession was stalled, and

I looked closely.

The first one I caught sight of was Doctor Postremo.

A shiver of fever shook me.

He was sitting in front, with his hands tied behind his

back. His now snow-white ugly ape-head with coal-black thick

brows and whiskers sat deep in his shoulders.

His eyes were filled with mortal fear, and his broad

mouth stood wide open.

Doctor Postremo!

“Samson won’t be able to cope with that hunchback!”

The crowd shrieked with laughter.

“They will have to pull out the pumpkin for that one!”

answered a second. “Hey, old man? Don’t you think so, turtle?”

Postremo made a ghastly face, closed his mouth,

gratingly moved his jaws, and then spat in the face of the man

who had addressed him.

A burst of laughter flew up.

“Bravo! Good aim, hump!”

Two soldiers pushed back the angry man, who, with his

disgusting face covered in spit, wanted to get on the cart. Next

to the Italian sat an old, venerable cleric in a torn cassock,

behind him was a stern-looking man in a blue silk jacket

embroidered with dull silver, and a gaunt lady who moved her

lips in prayer. The last seat on the cart was taken by a former

officer from the Flanders regiment and a young man, smiling

indifferently and contemptuously in a morning suit. The officer

bit his lips angrily and said something to his neighbor, who

answered with a shrug of the shoulders.

Immediately the cart started to move, rumbling and

skidding into motion, and the crowd sang a wild song unknown

to me, that roared down the alley. The soldiers put their short

pipe stubs on their big hats and sang along enthusiastically.

Without will, driven forward by an irresistible force, I

stepped into the middle of the crowd behind the executioner’s

cart on which sat the wretch who had robbed me of the

happiness of my poor miserable life with his satanic arts.

Nevertheless, I felt no resentment against him, as much as his

look reminded me of the greatest pain that I had ever suffered.

But now I felt as if he had only been the tool of an inscrutable

power which had directed everything as it had come. It also

seemed to me that the terrible end to which he was now rolling

toward on the shaking seat of the cart was not in the light of a

punishment that had been executed on him, but as a redemption

for this poor, wicked spirit, bound in a misshapen body.

Between these more foreboding than clear thoughts, was the

inexplicable feeling that moved all the people here, the terrible

and unfathomable desire to witness a terrible operation on

others, which in this time of great death and uncertainty of all

fate, excited great interest because without a doubt many of

those who today walked along freely and safely might in the

very near future experience the same.

In these minutes, the revolution, which I had longed to

see close up, was seen as something unspeakably horrible and

terrible. It was as if one had unleashed vicious animals against

sentient human beings, creatures of the lowest kind, which

cannot get enough pleasure in the suffering of their fellow

beings, as if demons from the depths had united, to eradicate

their former tamers and rulers and with them to exterminate

every order. What I saw in the reddened, eye-twinkling,

distorted faces around me was not humanity. Then I saw the

young nobleman and the officer on the rearmost seat, but also

from these victims a cold wave flowed toward me. They were

evil in their hearts to the last. It was obvious that to them the

people in the street were the same as the cobblestones, the dirt

that stuck to the high wheels of the cart, or the half-starved dog

that yelped and jumped around the harnessed mares.

In my desolate misery and in the burning pity that almost

burst my heart; I nevertheless knew clearly that in the last

feelings of these two on the cart lay all their guilt. They had

despised all people, God’s creatures as well as they, all their

lives and still despised them in their own bitter hour of death,

because they were unclean, uneducated, sweaty and lousy.

These nobles did not consider that their own insensitivity had

made of them what they were: a horde of half-animals, who

had to defend themselves against the cruel scourge of poverty

and being outcasts.

Posted in Uncategorized | Tagged books, fantasy, fiction, life, writing | Leave a Comment »

The Rebirth of Melchior Dronte by Paul Busson and translated by Joe E Bandel

“A knife hangs – falls -. -Ah!”

A shriek came from her mouth. She squirmed in her chair,

half opened her eyes, so that one could see the whiteness,

jumped up briefly in the chair and fell back heavily.

Everybody had jumped up.

“A hysteric,” someone said loudly.

“For today the demonstration is finished,” sounded the

voice of the man standing next to her. “I hope that the

gentleman has not been left unsatisfied, namely the gentleman

who has had his rooster stolen.”

Someone gave a forced laugh.

Everyone was pushing towards the exit, pursued by the

sneering looks of the pale man.

I looked around once again. The girl was awake, looking

around confused and astonished.

A shiver ran down my spine, as if death were standing

behind me. We hastily descended the stairs.

“It’s a pity I didn’t ask to know the day of my death,”

crowed Magister Fleck. “Could have made my dispositions in

good time.”

“You did well to omit that question.”

It was Doctor Schlurich who spoke these words.

No one made any reply.

In the thick, gray river fog that rolled through the streets,

we parted.

Silently I walked next to Doctor Schlurich.

“I suspected that she was deceiving me. But it hurts when

you know for sure,” he said softly.

He shook my hand and disappeared around the next

street corner.

Far and near sounded the calls of the patrols and

watchmen.

“A knife hangs – then falls -“, The Pythia had shouted.

Icy cold crept under my coat and shook me. The handle

of the bell pull at the inn was a small, brassy hand, a small,

cold hand of death.

When my extra mail coach had crossed the French border,

and the horses had to be fed and watered in a respectable spot, I

went to the inn and had an egg dish prepared for me.

The tables around me were full of people. Carters,

peasants, merchants, burghers and craftsmen were discussing

with all the liveliness of their nature the latest incidents, the

increasing frequency of executions. Recently, very close to this

place the castle of a very haughty and extremely hard-hearted

Viscount against lowly people, was stormed by the peasants

and after a thorough plundering was set on fire. Some of those

who drank the thick red wine openly boasted of the deeds they

had committed.

When I heard how beastly the people had been in the

priceless library and in the picture gallery of the castle, how

they had used the porcelain as chamber pots before smashing it

as night crockery, I had to think of the words of Doctor

Schlurich, who warned me against observing revolutions at

close range. Then, when a very ugly, badly scarred fellow

started to boast, bawling, how he had speared “Bijou”, the

favorite dog of the lady of the castle, on a pike and carried it

around squirming alive for an hour whimpering, until it finally

died in pain and fear, I was seized by a furious anger against

this two-legged beast.

But immediately, like a black cloud, the memory of a dog

fell on me, whose faithful love I had destroyed in a senseless fit

of rage with a deadly stone throw. No, I had no right to be a

judge, even though I had only acted in a violent fit of temper,

but this man, however had acted in diabolic malice.

Tormentingly the thought rose in me that there were people

who were evil by nature -. What should happen to them?

“Melchior Dronte!” fluted a repulsive voice. “Melchior!

Beautiful Melchior!”

I was so frightened that I almost knocked my wine glass

off the table.

I looked to where the voice had come from, and saw an

old woman, covered with dirt and rags, sitting at a table. She

had a box of multicolored slips of paper sitting next to her,

from which a short pole with a crossbar was sticking up. But

on the wood sat a parrot, in whose blue-gray, wrinkled skin

only a few quills were still stuck, while the large head with the

rolling eyes was wrinkled and completely bald. The woman,

noticing my gaze, hurriedly stood up, approached my place and

after she had slung the strap over her shoulder, blew her

burning breath into my face:

“Beautiful, young Herr, Apollonius will tell you

prophesy!”

Despite her pitiful appearance, the dripping drunkard’s

nose and the inflamed eyes I recognized in her the beautiful

Laurette and in the parrot, the monster of the Spanish Envoy. A

sharp pain went through my heart when I compared the image

of Sattler’s Lorle against this gruesome, lemur-like apparition.

Although the infernal parrot had called me by my name, there

was not a spark of memory in her poor, devastated face. Instead

I recognized in the squinting look of the bird such a rage that I

could not free myself from a feeling of fear. The dull, old

woman, who had once been young, rosy and innocent in my

arms, looked at me out of half-blinded eyes and repeated the

slurred phrase from before. I slipped a coin into her gouty

fingers, which she put in her mouth in a disgusting way for

safekeeping, and I saw with satisfaction that for the time being

no one was paying any attention to us.

“Sicut cadaver -,” chuckled the bird. “Kiss her like a

corpse, fair Melchior!”

I approached him and said, as if speaking to a human

being:

“May you soon be redeemed, poor soul!”

Was it really I who suddenly found these words?

The parrot looked at me with a fixed gaze. All malice

disappeared from his eyes, and two large tears rolled down his

beak, as I had seen before. It was eerie and poignant beyond

measure.

“Misericordia,” he groaned. “Mercy!”

And then he hurriedly climbed down the short pole,

rummaged back and forth with his beak in the colorful papers

and grabbed a fiery red one, which he held out to me.

I took the paper from his beak and gave the poor Laurette

a gold piece and nodded to her.

Not a ray of remembrance flickered in her features.

With her box, on the crossbar of which the parrot

lowered its head on her bare breast, she shuffled to the nearest

table.

“O mon Dieu!,” cried the parrot, and the hopeless tone of

this lament went through my marrow and legs.

“Keep your basilisk quiet, you old bone box,” cried a

carter in a blue smock at the neighboring table. “No one

understands its own words. There are no loud aristocrats here,

who take pleasure in such silliness!”

“Why don’t you turn the collar on that stinking grain-

eater, Blaise?” shouted a miller’s boy covered in white dust.

“And if you get your hands on an aristocrat, by the way –

I’ll be happy to help you!” he said, half aloud, with a wry look

at me.

Startled, the old woman limped away from the table and

huddled in her corner again.

I observed the people, who were mainly given to boastful

speeches and certainly not all of them were malicious, and

drank my wine slowly. Besides, I had to wait for the new mail

coach driver before I could continue my journey.

I put the red square slip of paper from the box of the

beautiful Laurette down on the tabletop, and although I told

myself that such things could have no meaning at all, I had to

remember that Apollonius had selected this note for me and I

wanted to pay serious attention to it. In bad print under a series

of astrological signs was written:

“There is a great danger threatening you, which is not in

your power to ward off. A tremendous change will happen to

you, but fear nothing: for you it will be nothing more than the

precursor to a new life.”

I could not see anything else in this writing other than the

ambiguous and naturally quite indeterminate nature of such

fortunes which are given for a piece of copper, and selected

from the heap of similar ambiguous sayings by an animal

which is usually trained for this purpose, nevertheless this

small piece of paper moved me in a significant way. And even

though I was distressed at Laurette’s fate, the fate of so many

careless and frivolous girls and women, I was almost more

moved by pity for the soul, which in a miserable, slowly dying

bird body had to atone for a terrible sin unknown to me. I was

heartily pleased when the new mail coach driver, a young

Frenchman adorned with the tricolor cockade, came in and then

politely asked me to get ready for the onward journey.

As I left the room, it was as if I heard scornful laughter

and swearing aimed at me. I made an effort to remain

completely calm and to excuse the groundless bitterness of

people because of the injustice that had been inflicted on them

for many generations.

I was quite happy when I drove away in the coach.

Admittedly, I was accompanied by all kinds of heavy thoughts.

The sight of my former playmate, whom I had left in splendor

and glory in Vienna and found her here as a pitiable, and

trampled person deprived of reason, and even more the eerie

encounter with the ghostly bird Apollonius, in which a damned

soul was atoning, and lastly, the painful observation that

undiscriminating hatred and blind vindictiveness rose up like

an ugly layer of mold in this image of a great national

revolution – all this saddened me very much and almost made

me regret having undertaken this dangerous and exhausting

journey. But at the same time, I felt the compelling necessity of

a fateful decision, which drove me on and perhaps even more

than that: the desire that came from the depths for the

fulfillment and completion of what I had been destined to do.

Also the conversation with the new coach driver, which

he began with me, half turned back, did not help to cheer me

up. He saw; that I was a gentleman of distinction, and in spite

of the drivel about freedom and equality, this was a source of

refreshment to him. Every day he had to deal with the lowest

classes of society, who made big words and boasted of their

bad manners. Nevertheless, the farther we got into the country,

the more he wanted to advise me all the more urgently to howl

with the wolves and in particular not to meet in public places,

as I had just done, to stay away from the mob. Nothing irritates

the rabble more than silent disrespect, for which the otherwise

thick-skinned fellows have an exceptionally sensitive feeling.

There was nothing else to do than to leave pride aside and be

fresh with every brother and pig. For the time being, only the

most hated and well-known oppressors of the common man,

who succeeded in getting away with their bare lives, should

still be happy. But as the signs were, it would soon go against

all the nobles, but then also against those who were

intellectually superior to the lower people, since they were

considered protectors and friends of the old order. Whether the

individual lived righteously and honestly, whether he perhaps

had even been a faithful helper of the poor and oppressed, or

even suffered hardship for their sake, blood-drunk mobs did

not think about that.

Posted in Uncategorized | Tagged books, family, fiction, short-story, writing | Leave a Comment »

The Rebirth of Melchior Dronte by Paul Busson and translated by Joe E Bandel

“Maybe so, maybe so,” growled a fat, frowning man with

a coarse face and a high collar. “Nevertheless, it would be a

mistake to consider the not yet confirmed fraud from the outset

as a premise. We are man enough to get to the bottom of the

thing, and I’m not concerned with light phenomena or

nonsensical tapping.”

Just then, a small wallpaper door opened, and a

somewhat crooked, elderly girl with an unattractive and yellow

face entered. She was dressed in a gray silk robe and sat down

in the arm chair after a curtsy to those present, spreading and

smoothing her skirt.

Behind her stepped a darkly dressed man with an

unpleasant facial expression and piercing eyes, whose age was

between thirty and forty, not far from that of the woman. In his

face, strangely enough, the facial expressions changed

constantly, so that one could believe, his mood swung between

laughing and crying. He bowed, collected the required douceur

on a silver plate, put the plate in front of one of the candelabras,

bowed again and then said with a hard accent, as it is peculiar

to German-speaking Russians:

“This Demoiselle Maria Theresia Köckering, from Reval,

38 years old, is capable of answering all the questions

addressed to her, whether they concern the past, the present or

future of the esteemed personalities present here, once she has

gone into magnetic sleep.”

He approached the table, extinguished some of the

brightly burning wax candles, then went to the motionless girl,

stretched out his fingers toward her face and softly stroked her

forehead, eyes and temples several times. Then he turned

around.

“She’s asleep now,” he said.

We looked at her and had the impression of a seated

person deeply lost in sleep.

“I beg your pardon, my highly respectable gentlemen!”

continued the man in a subdued voice. “There is a certain

amount of silence required for the experiment. If the questions

asked are answered well I ask you to confirm half aloud that

the answer was correct. If it is not, I ask you to point out

without agitation, whereupon I will renew the question. For it

happens that the sensitive mind of the demoiselle can

experience confusion caused by scary images from other

regions. Any fair examination and investigation is permitted.

Strictly forbidden is disturbing noise, rough calling, abrupt

touching, since physical fright endangers the life of the

demoiselle in the highest, because in such a state the soul is

only very loosely connected with the body.”

A short, disapproving clearing of the throat came from

the row of listeners. But the presenter did not pay attention to it,

but continued speaking:

“For the time being, I will ask some questions myself. So

that the learned audience will understand the simplicity of the

process and the impossibility of fraud.

“Demoiselle Maria Theresial” he addressed the sleeping

woman in a raised tone.

In a moment, the face of the sleeper began to twitch, and

her hands moved restlessly back and forth, grasping at the air

and in turn fingering the armrests of the chair.

“Do you hear me, demoiselle?”

“I hear,” she said with a strangely altered and deeper

sounding rough voice.

“The names of the distinguished and learned gentlemen

present here in their seating order from right to left?”

To us he said behind his held out hand.

“She sees everything as it were in a mirror, and that’s

how she calculates.”

The trembling and grimacing became more severe, then a

kind of smile appeared flippantly on her face, and she spoke

inexorably, rapidly and without any pause in between:

“Doctor Achaz Moll, Professor Gisbertus van der Meulen,

Doctor Johannes Baptista Schlurich, Baron Melchior von

Dronte, Magister Benedikt Fleck, Spectabilitas Doctor Imanuel

Balaenarius, Doctor Veit Pfefferich.”

A murmur and nod of approval followed. But Magister

Fleck said half aloud, such knowledge can be obtained from

such highly famous men.

The man with the sleeping woman shook his head with

an angry expression and asked a second question:

“Tell me, demoiselle, on what important work that

gentleman is currently working on, who is raising his hand?”

He gave us a sign, and Spectabilis raised his hand,

silently invited by all.

Köckering became lively again, moved her lips, put her

hand up several times and then out:

“About the healing effect of pure water in case of

Obstipatio and about the harm of too frequent purging.”

“Bene,” said the dean, “Admirable!”

“This, too, can be brought to light – “, whispered the

suspicious red haired magister.

“I now ask the honored gentlemen, to ask your own

questions as you see fit.”

The magnetizer looked with a sharp glance at the

magister and with a wave of his hand motioned him to speak.

“How — how much money do I have in my pocket?” the

latter stammered, visibly surprised.

The woman answered without reflection:

“One Laubtaler, but it’s fake, and five silver groschen.”

The questioner pulled out his little pouch and counted the

small amount of cash. It was true.

“Quite nice,” grumbled Doctor Moll, and his double chin

rested gloomily on his high tie.

“When he asks for his pennies, is it as well to inquire

who stole my reddish-brown rooster from my house six days

ago?”

“Leberecht Piepmal,” came back immediately.

“That thunder may smite you!” the coarse voice started

up. “That must be true! I immediately said to my beloved, that

Piepmal and no other –“

“Piano, my lord,” the organizer admonished unwillingly.

“Just not too loud! Another of the gentlemen, if you please”

“On which day of the week, month and year did the

woman I loved the most pass away?” one of the gentlemen said

softly.

The face of the sleeping woman distorted painfully, her

mouth closed tightly, and after a while she understood:

“Wednesday, the 12th of Hornung 1754.”

“My mother!” A heavy sigh said, that the question had

been answered correctly.

I took heart and raised my voice:

“Who visited me there, from where I came to this city?”

The sleeping woman stroked with her hand the back of

the chair, shook her head softly, and then let out a sound like a

soft laugh and spoke:

“You yourself -” she said.

A murmur rose.

“Attention, Demoiselle!” sounded the commanding voice.

“The gentleman himself could not have done it. Once more!”

“Isa Bektschi – yourself — your brother in you-.-” she

whispered, barely audible, “Ewli -“

“I ask, my lord, whether this answer is understandable to

you?”

I nodded mutely.

“But we don’t understand it,” the magister blurted out.

“What do you mean by that?”

“What do you mean demoiselle?” the man repeated

readily.

“The coming back,” she breathed.

“She babbles,” grumbled Doctor Pepperich.

“Still, some things have been amazing so far. May I do

one more question?”

“Please.”

“What is it? It’s on my desk at home, once alive and very

clever and is now useless and dead.”

The magnetized one breathed heavily, thought

strenuously and reached out with her hand to her throat,

catching her breath with difficulty, as if a choking attack was

coming over her. Then she said heavily:

“The hand – of the – hanged Janitschek from Prague.”

The doctor passed a blue cloth over his sweating

forehead.

“Guessed,” he gasped. “The hand of the Bohemian thief

lies withered on my table.”

“It is astonishing, after all,” Dean Balaenarius cleared his

throat. “The phenomenon is not so easy to grasp -.”

The man in the dark habit stepped forward.

“My esteemed ones,” he said. “The Demoiselle is greatly

fatigued and in need of early rest. May I ask for a few more

questions about the future?”

But no one moved. No one seemed to have the desire to

look behind the dark veil.

Then Doctor Schlurich half rose from his seat, opened his

mouth, wanted to speak, but changed his mind and sat down

again.

“Right now he is with her,” said Köckering tonelessly.

The doctor made a defensive gesture, as if he didn’t want

to hear anything, and leaned back, deathly pale, with quivering

lips, in his chair.

“That was her oath-!” I heard him say softly.

“May I do one more question?”

I stood up. So far I had remained so dazed by what the

clairvoyant had told me that everything around me was as if in

a dream, but only at the surface, as I had been lost in my own

thoughts.

A silent, somewhat impatient movement of the hand

invited me.

“When will I see Isa Bektschi again?”

I asked.

The demoiselle raised her head, shuddered inward and

groaned.

Posted in Uncategorized | Tagged books, fantasy, fiction, short-story, writing | Leave a Comment »

The Rebirth of Melchior Dronte by Paul Busson and translated by Joe E Bandel

With that, he stood up, told me to eat the meal he had

ordered, a chocolate pudding with jams, and then to go to sleep.

I saw him slowly leave the room, with a friendly face,

holding a stick with a golden pomegranate daintily pressed to

his chin. After a few days I got up, and this all the more gladly,

as in the last days various noises, coming from the outside,

such as shouts, whistles and voices, had disturbed the silence of

my room.

With the help of the servant of the inn, I dressed and had

my hair done, during which I perceived that the silver hoop of

old age had fully descended on my head during my illness. The

good-natured servant told me many horror stories from France,

where blood flowed in streams and a human life was not worth

three pennies. The plague of the frenzy for freedom was

already spreading, and even in this otherwise calm and quiet

old-fashioned little town, all kinds of disgusting and unpleasant

things had happened in the last few days, which had been of

the journeymen and the erection of a liberty tree. However, the

city council had wisely submitted a petition to the highest

authority for cavalry and a battalion of infantry, which, as the

princely book keeper Gailer had informed him confidentially,

should be complied with as soon as possible.

When I had finished, I slowly descended to the dining

room and found there at the common table, to my great delight,

Doctor Schlurich, who immediately left his place and sat down

next to me.

We naturally got into a conversation about the exciting

events in the city, which had become like a faint flame to the

immense blaze of purple in France, but still seemed worthy of

attention. I said that I felt a great desire to go to the city of

Paris, to study the immense changes there at close quarters and

observe them. I could not conceal from him that the movement

that had begun there was of great interest to me, was

meaningful for the whole of mankind and downright promising.

Doctor Schlurich looked at me with a very thoughtful

look and said that he was somewhat surprised to see a

nobleman from an old and famous lineage see anything but

cheap disgust in these events. The profound upheaval which

was only in its infancy could not possibly be welcomed by a

caste whose privileged existence rests on an artificial nimbus

and a carefully sanctified tradition. He asked me, however, not

to misunderstand him. Because his initial astonishment about

my behavior was a thoroughly joyful one.

I replied that I had suffered a self-inflicted humiliation in

my youth that had given me the opportunity to go to school

among people of the lowest classes, which, whether it was

good or bad, had given me the opportunity as a student of

freeing myself from all arrogance and conceit of status. In

addition, I had gained the valuable awareness that the so-called

differences in standing were created by artificially erected and

easily removable barriers, which had arisen and were

maintained, to deprive the children of the poor from any better

education and the cultivation of their noble feelings, which

later on resulted in their crudeness and ignorance. The

undeniable merits of the society to which the nobility and the

refined bourgeoisie enjoyed, were only the result of a carefully

conducted education. If this could only once be shared not just

with the privileged classes, but with all members of the human

race, humanity would not only protect itself with the noblest

weapon, but it would also bring an immeasurable abundance of

talents and abilities into a new light that has never existed

before. Indeed those places, where they shyly blossom in spite

of all the pressure, and are suppressed as dangerous to the state

without any knowledge.

“You are a nobleman in the inner sense of the word,” said

the doctor and bowed.

I felt the blush of shame rise to my face, and silently I

thought of many things in my life, which were of an ugly

nature and would always remain as stains on me.

“However, cher haran,” the doctor continued, “I don’t

know whether, if you were to ask for my advice, I would advise

you, to witness the great upheaval in the immediate vicinity,

that is to say, in Paris. Consider:

If one cleans a neglected place in his garden, in order to

grow useful and lovely plants, and removes the old stones and

debris, ugly worms, woodlice, centipedes and all kinds of nasty

creatures, which now crawl from their dark places, run around

and fall on each other in sudden greed. So it is also with those

social changes that are called revolutions. Until the noble core,

the light of freedom, shows itself, there is abominable work to

be done, which perhaps people can only see who look back

after many years, but to those who experience it, their souls are

filled with such horror that they no longer recognize anything

else, and even lose hope. Revolutions are filled with filth,

blood, shouting, evil deeds, wild development of the animal

instincts and base greed, and it takes a long time for the jet of

fire that shoots up to become pure and free of filthy cinders,

and the dominion of the senseless to move into the hands of

sensible men.”

A wild yelling and screaming outside the windows

interrupted him. In the dining room there was a hurried pushing

back of the chairs and jumping up. One saw people outside

walk by on the street, first individually, then dense masses, and

behind them came a closed united front of dragoons, which

struck with the flat of their swords and thus cleared the street.

All this passed quickly, the shouting and the clattering hoof

beats on the cobblestones disappeared, and in a few minutes

the street was quiet again, covered with lost hats, sticks and

other things.

“Our good Germans are slowly maturing,” Doctor

Schlurich returned back to the table. “And many a thing will

still pass over our people, until they are able to assert inner and

outer freedom, from which, by the way, even the French will

still be without. The merit, however, of having made a start

could be left to them, if one did not have to concede it from the

standpoint of higher justice from the English viewpoint.

Nevertheless, Herr Baron: The Germans will, after much

suffering and hardship be the chosen ones, from whom the

salvation of the world emanates. This is my belief.”

We were silent for a long time, and our conversation

turned to other things. I learned that Doctor Schlurich, born in

Köllen, had settled here, not so much to earn money, which in

his circumstances was not necessary, but in order to calmly

work on unknown phenomena of a psychical nature, with

whose research he was mainly concerned. Here he had made a

very special find. Namely, in a house of the city lived a

Demoiselle Köckering, who, in the company of various doctors

was often put into a magnetic sleep and in this state was asked

questions about the past and the future, as well as the most

diverse things to which she answered completely and correctly.

If I happened to be interested in such secrets of nature, which

only the unintelligent can connect with ghosts and devils, it

would be easy for him to introduce me there. Since the person

must be kept secret and lives from her art, it is, however,

customary to give a douceur in gold at the first entrance.

I was immediately ready to be led by him into the house,

and thanked him for his trust.

When it began to dawn, we went on our way.

A cool, damp wind was blowing from the Rhine. The wet

air penetrated chillingly through our coats. In several streets we

were stopped by patrols on horseback with loaded carbines, but

were allowed to pass as persons of distinction.

After some wandering we found the house “Zum

silbernen Schneck”, in which the demoiselle lived.

Only after knocking several times was the door opened to

us by a man, who was finally able to hide his hesitation for fear

of the craftsmen and ship’s servants, who, together with the evil

folk from the taverns, hooting “Ca ira” and hammering on the

gates, had raged in the alley a short while ago to get the

prostitutes living in the house next door and take them with

them. Soldiers would have quickly driven the screamers away

and then would themselves have gone through the door with

the red lantern.

We climbed the narrow staircase by the light of the

tallow candle that dripped between his fingers, and after a

special kind of knock, were led into a bright, octagonal

chamber, whose windows were tightly curtained. There was

nothing to be seen in it but an armchair upholstered in worn

brocade, next to which, on two small tables, burned many-

armed candlesticks, and in front of it a row of ordinary wooden

armchairs, on which some men sat waiting. They turned their

heads toward us. Both could be easily classed among the

scholars by their dress and the expression of their faces.

Doctor Schlurich and I approached the waiting people

and gave our names, which was answered in the same way.

“-especially the prophecies of the demoiselle should be

strictly examined,” one of the gentlemen, who was addressed

as “Spectability” continued his speech, which was interrupted

by our entrance.

“All the more so, as the man who pretends to put her into

a magnetic sleep collects one louisdor per person. My esteemed

colleague Professor Fulvius, who watched the demonstration

was not satisfied in all respects. Those bluish efflorescence’s

which you could observe perfectly, on the hands of

Emmerentia Gock in Ebersweiler, who is said to be possessed

by the devil, are completely absent, and everything that is

going on is just limited to some at times certainly astonishing

messages about the lives and fates of the people present.”

“Whereby it is respectfully to be noted,” said a small,

skinny man with a reddish wig in the highest falsetto “that the

prophesies of the woman, in so far as they refer to the future,

are completely worthless scientifically, because at present they

are unverifiable.”

Posted in Uncategorized | Tagged bible, faith, god, jesus, writing | Leave a Comment »

The Rebirth of Melchior Dronte by Paul Busson and translated by Joe E Bandel

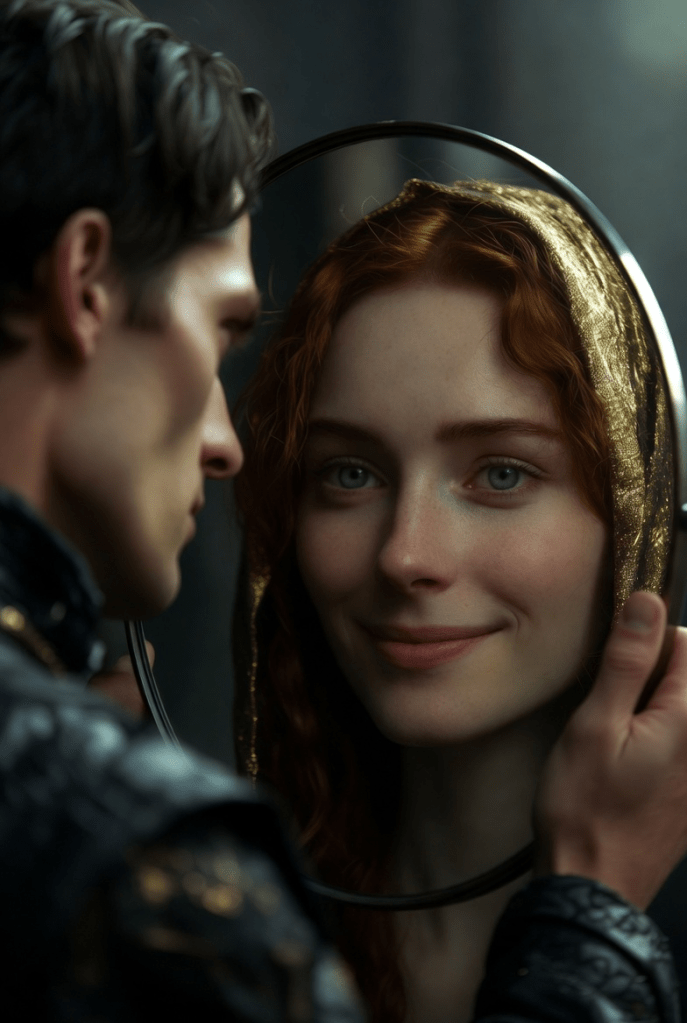

With paralyzing horror I looked myself in the face, saw

how greedily and flickeringly my eyes burned, how my mouth

was narrow and angry and spoke with cruel calm:

“Weinschrötter, you come before the Inquisition in the

second degree, I ask for the second time:”

“Will you confess or not?”

A cry of pain came from her mouth, but she shook her

head in denial, so that a red flag waved around her.

The one with the cowl scraped in a basin of glowing

embers, and pulled a white-hot iron from the coals.

Then smashing and crashing the terrible image collapsed.

The mirror had slipped from my hand.

Splinters and shards lay scattered on the floor.

The magister entered and said:

“Baron, I’m afraid this means seven years of bad luck!”

“I want to get up and leave,” I ordered. “Get me a

carriage. I don’t want to spend another night in this room.”

“You are too weak, Baron,” he said and then added. “I

know a carriage. The driver Peter will be happy to hitch up if I

send him mail. But it’s a long way to the next town.”

“Get me a carriage,” I urged him. “I’m not staying here.”

He walked out shaking his head.

I was afraid in that room. The man from the Orient had

appeared to me here with a comfort that outweighed all the

sufferings and wanderings of my life, yet demons dwelled in

these dilapidated walls, which were hostile to all living things.

The screams of pain, the curses and lamentations, which still

haunted the tattered leather wallpaper, were hiding in the

cracks of the wall and in the twilight they were like the buzzing

of mosquitoes, yet they had still not succeeded in deluding me

into believing that I had attended a coven, that I was among

larvae. I listened up and let the magister tell me the miraculous

things that the people, tired of the zealousness and the

artificially created crisis, had already accomplished in this

country, and when he, with fiery eyes and a face that I did not

recognize, swore high and dear, that the bright dawn of

freedom would rise from the smoking and stinking debris of

the shattered fortresses, this description moved me so much

that I felt a desire to see the events in Paris with my own eyes.

Supported by the Magister, I climbed down the

crumbling staircase of Krottenriede for the last time and

knocked on the door of the master of the hound.

He was sitting at a table, whistling to himself and looking

at the components of a gold-inlaid rifle lock, which he had

taken apart and anointed it with a feather from a small bottle of

clear bone oil.

When he heard of my intention, he did not want to know

anything about it, and said that now the fun days of stalking the

red buck would begin and that he wouldn’t like it if the son of

his old crony Dronte left without a successful hunt and with

such an abrupt departure. And as for taking that maleficent

fellow, the windy magister along with, it was completely out of

the question, since he will be taking the next few days, to write

various sharp manifests to the farmers all around, whose dogs

would again begin to prowl and roam around and this must be

stopped immediately and punished with severe punishments.

I replied to him very politely that I could hardly be

restrained from staying on Krottenriede, especially since I had

important and urgent business. Otherwise it would hardly occur

to me to travel for miles on a farm wagon in a state of half

recovery. If he were to take it upon himself to leave me in my

infirmity without any other companion than the waggoner, then

this was a matter that he would have to decide with his

conscience.

These words struck him to some extent, but nevertheless

he swayed his head back and forth and said that he did not like

to let the magister out of his hand. I, as a nobleman, must

understand that such good-for-nothings, when they get the

chance would make an attempt to escape. He had confronted

the journeyman with the fact that a couple of times the wood

invoices had not been correct, for which he, the master of the

hound, was himself to blame, nevertheless, it occurred to him

that he could threaten the windbag, on the basis of this fact, pay

him less and let him walk into the hole until he would willingly

return to food and whip. Because, added the old swindler with

a wink, he would never get such a cheap and good scribe in his

life, and for that very reason, he could not let the man out of his

sight.

I stopped and asked him once again to allow the man as

my escort, he finally gave in after some cunning consideration

and said that he already wanted to authorize the windbag and

give him papers so that the rascal with his severed ears would

have to return immediately after he had brought me to my

destination. But he wanted to advise me one thing: to treat the

imaginary one, the scholarly monkey no differently than a pot

de chambre, porter and lackey, and on occasion not to spare a

few kicks or face slaps. For this is the best medicine for such

birds, who secretly think they are better than a nobleman or a

good soldier.

I shook his hand and asked for a temporary leave; so that

he could think that there was still time and that I would start

packing. Instead of partaking in the upcoming lunch, I waved

to Hemmetschnur, who was anxiously waiting in the

antechamber, since he had always been forbidden to enter the

manorial chambers with the exception of the dining room, and

quickly climbed with him onto the waiting carriage, which the

young farmer on the driver’s seat at my command immediately

set into motion.

We rattled down the steep road and were only a few

thousand paces from Krottenriede when a loud bugle sounded

from the heights.

The farmer made an effort to stop the horses, and said:

“The merciful lord is calling us back!”

“You fool!” said the magister. “It’s only the hunter Räub,

who gives a farewell to the high-born gentleman next to me.

Therefore, be quiet!”

So we drove on, and soon the blowing died away, in

which I well recognized the call “Rallie”, in the fresh wind.

In the afternoon, we stopped in a little village.

My weakness increased considerably. Half asleep I

listened to Hemmetschnur, who, after he had gained so much

confidence, told me the story of his cut off ears and how this

had been a severe punishment for a stupid prank he had

committed in Stambul, when he had responded to the waving

and nodding of a Turkish, veiled lady, by climbing over a wall,

and was immediately seized for the cuttings and, at the

command of a man in rich clothes, was wounded by two

burning cuts with a hand-held scimitar, which one of them

pulled out of his belt, and was deprived of his ears. When he

collapsed from pain, weakness and loss of blood, the cruel

man’s servants dragged him out into the deserted street, in the

sweltering heat of the noon, and threw him on a heap of dung

and rubbish, where he remained. Towards evening he awoke

and felt how the fierce wild dogs that they have there in all the

alleys licked his wounds for the sake of blood, and this was the

reason that no inflammation appeared. A compassionate

Muslim picked him up and took him to a Franciscan monastery,

where he was cared for.

And the most distressing thing of all was that he learned

later that the veiled lady had been a nasty old hag who had

wanted to have some fun, which was made worse by the arrival

of her son-in-law, a Pascha as powerful as he was violent, who

had brought it to such a miserable end.

I was not able to take food and I kept seeing the cut off,

shell-shaped ears of the magister in front of me, and how

shaggy dogs fought over the bloody pieces in the yellow dust

of the street.

When we arrived in the Rhenish city toward evening and

the carriage was parked in front of the door of the inn “Zum

Reichsapfel”, I gave Hemmetschnur leave, although he was

very concerned about me and wanted to stay with me. But I

reminded him to cross the river before the city gates closed or

before a messenger on horseback from the master of the hound

came behind them.

Then he was so frightened that his teeth snapped open

struck one against the other. Once again he kissed my hand,

bowed many times and then pointing to the wide, calm stream,

said:

“I go to freedom, my patron! Wherever I see you again,

my Herr Baron, I will serve you faithfully and be yours with

blood and life!”

After I had amply rewarded Peter, the driver, who had

observed the departure of the magister with much head

scratching and frowning, I entered the inn.

“The gentleman is burning red in the face,” said the

waiter, who directed me to my room. “The gentleman should

go to bed; I will immediately call Doctor Schlurich.”

He helped me to undress, and immediately after that I felt

the hot waves and the shivering chill of the fever that was

setting in again. And then there was darkness around me, out of

which an endless procession of sights passed by me, even more

morose and sullen than the face of the magister on the day

when I had first seen him at Krottenriede Castle.

After long weeks of a bedridden life in which I barely

stirred, after countless days in which my inner gaze firmly and

unwaveringly held the image of Isa Bektschi, the hour came

when I, as if awakening from a deep sleep, saw doctor

Schlurich sitting at my bedside. He was a slim man of about

forty years, very distinguished and intelligent-looking, with a

high, clean forehead and beautiful eyes. His black suit was

made of the finest fabric, and in his tie was a bright green

emerald of great value, and his hands were delicate, white and

well-groomed.

“My lord baron,” he said in a pleasant and subdued voice.

“I am glad that your vigorous nature and will to live have won

the not easy victory over a severe nervous fever.”

“And your art,” I added politely.

“My skill can, at the best of times, support the secretive

forces with which the body can defend itself against the

impending decay, can even summon it, can alleviate pain and

restlessness, but must – with the exception of a few cases – as it

were, watch, how the quarrel surges to and fro. The friendly

fighters against death here and there with this and that means to

bring support (and it may be that this is sometimes decisive),

but on the whole the sick person must find the remedy in

himself or bring it forth. This time you, distinguished Herr,

were on the way into the shadow realm, and you have rightly

returned!”

Posted in Uncategorized | Tagged books, family, fiction, life, writing | Leave a Comment »

Chapter 27 Disaster

Llana looked at everyone in the firelight. “Are there any more questions?”

“So I meet you here next month at the same time?” Tobal asked.

“Right,” she said. “And I will give you the training you need to train Becca and Fiona.”

That was the end of the meeting, and they chatted the rest of the evening, sharing what had been going on in each other’s lives. Llana was very concerned about the medics being kicked off the mountain and the decision to build a permanent base at the old original gathering spot. She urged everyone to be careful.

The lake was beautiful, and they spent a lot of time skinny-dipping in the cold waters and lying on the beach in the sun, watching air transports bring workers and supplies to the gathering spot. With so much activity, it seemed hard to believe there was any danger in the area. Fiona seemed like a sister to him, and he was deeply in love with Becca. Their love was passionate. The days passed, and before he knew it, he had to head back to the cavern for the new moon tournaments. He urged the girls to leave the lake and warned them not to get too close to the waterfall—two were more vulnerable than three, and it might not be safe to stay.

The girls didn’t seem to take his concerns too seriously but suggested they might look up Nikki and see how she was doing with her last newbie. As Tobal left, they told him they were planning to leave the next day.

He was looking forward to his first regular meeting as a Journeyman. He found himself in the area a day early and thought he would check the camp out a little more. He was surprised to find several Journeymen already there. They welcomed him warmly.

Unlike circle, which was abandoned each month, there was always someone at this camp guarding it, hanging around in the caverns, socializing, sparring, or doing some type of assigned duty. They had a lot of time on their hands.

Staying in the camp was a way to socialize, work out, and practice. There was also a hot spring to soak in, and that was a luxury for sore and aching muscles. The tournaments were always scheduled early in the day and the initiations were scheduled closer to midnight. That was why Tobal had seen no tournaments on the day of his initiation. One of the caverns had been set aside as a fighting arena. It had soft powdered sand on the floor like beach sand.

There were a few medics wearing red tunics acting as judges or referees as well as emergency medics in case something went wrong. They took care of the many minor injuries that were common during these fights.

As the newbie of the group it didn’t take long for Tobal to realize how it worked. The referee laid out the ground rules, of which there were basically none. Anyone could challenge anyone to a fight. A person could not be challenged any more than one time in a day. However, a person could challenge as many people as they wanted to. It was set up in this way so if a person got beaten badly they would not have to fight again that night. But if they won and felt like it they could challenge someone else.

The oldest members by seniority got the first challenge and the youngest ones got the last challenges if they hadn’t already been challenged. Generally the older members took advantage of the inexperienced members by challenging them.

The first challenge was an old veteran that was burly and bearded. He was not well liked it seemed. He challenged Joy. It was easy to see why the grizzly had chosen Joy. He was almost twice Joy’s size. He clearly expected the match to be over quickly. Joy surprised him by being a lot faster, more elusive and more aggressive than Tobal had realized.

The brute simply couldn’t make contact with Joy and three times went sprawling as Joy tripped him during a rush but he always managed to fall within the rope circle and got back to his feet quickly. Every now and then a wild swing would connect and Joy would stagger. She simply was too light to do much damage to him. Tobal could see she was tiring and wasn’t surprised when a wild arm knocked her to the floor. The brute then sat on her and held her motionless until the referee called time and declared the brute to be the winner.

Joy really had trouble with this degree because of her small size and young age. So far she had only won three fights. The good news was that she was getting much better at fighting and she was also getting larger and stronger as she grew older. She was learning about fighting the hard way, by losing. Most of the older Journeymen had already challenged Joy and won. They couldn’t challenge her again. That meant gradually Joy was being more evenly matched as she grew in skill. The burly veteran she had just fought was undoubtedly one of the few older ones that hadn’t yet been able to challenge her. The entire thing made Tobal feel slightly sick.

Next up was Ox. Ox smiled maliciously as he challenged Tobal.

“You don’t have a knife to save you this time,” he sneered.

Tobal felt a weak sick feeling in his stomach and realized he was probably in for quite a beating. Ox still held a grudge against Tobal from that time in sanctuary when they had argued over Fiona. Tobal had only saved himself from a beating by instinctively pulling a knife and threatening Ox with it. This time though no weapons were allowed. It was simply hand to hand warfare with no rules.

Tobal assumed a boxer’s stance and tried a few jabs to no effect. Cautiously they circled the ring looking for an opening. Then Ox put down his head and charged straight at Tobal. He tried moving out of the way but was caught by a huge hairy arm that turned him around. Next a hammer exploded in the pit of his stomach and solar plexus doubling him up. He felt the bile rise in his throat as all the fight ran out of him. He lay in agony on the cave floor gasping for breath curled up in the fetal position trying to protect his stomach from further damage. Dimly he heard the referee call out time. Tobal had just lost his first match in less than two minutes. His eyes were stinging with tears.

Tobal was surprised when Joy re-challenged the brute from the first fight. It was easy to see there was no such thing as fairness in these matches. Anybody was fair game and the smaller and weaker got picked on more often than the bigger and stronger ones. If you were big and powerful things generally went your way. It didn’t seem right but life was unfair at times and the strong often did win. It was brutal survival of the fittest in it’s most primitive form and wasn’t very pretty.

Tobal tasted blood in his mouth as he sat watching Joy. She handled herself remarkably well this time and it was easy to see she had more stamina than the brute. She found an opening and finished the match by landing a kick solidly in the groin of the brute to the applause of the watching crowd. It was then that Tobal realized he had to be really careful. He had to learn a heck of a lot more about fighting than he knew right now. He also realized Joy was right in fighting after her first defeat. It was the only chance she really had to move ahead and it didn’t cost her anything.

He looked over the unchallenged members of the group carefully. Being a loser he had the opportunity to challenge and in a spark of anger challenged one of the remaining members that hadn’t fought yet. In a burst of fury and lightning movements he had tripped and thrown the person out of the ring over the rope. The referee called the match and Tobal was the winner. In a flash of sportsmanship he went over and helped the other person back to his feet and they started talking together.

“Man, what got into you?” The other person said. “You were like a demon or something. I never even had a chance. It was all over before I knew what was happening.”

“That’s how my fight with Ox went,” He laughed. “I never saw it coming either.”

His name was Jake and soon he and Tobal were hanging out together sparring and learning everything they could from any of the others that were willing to spend time training with them. Tobal really sucked at fighting and it was good to team up with someone willing to work hard with him. They spent most of the next two weeks sparring every day for hours. They mercilessly drove themselves to the point of exhaustion. It seemed to Tobal that he was always stiff and bruised but when circle finally came he was ready for it and felt that he needed a little break.

While the tournaments were brutal, the initiations were beautiful in their own way. Tobal watched in fascination as the circle was cast widdershins and the pentagram was drawn upside down. The power was raised, but it felt different and had a harder edge to it.

The primal earth energy of the Journeyman degree was much different than the spiritual light energy of the Apprentice degree. It was more visceral and seemed more magickal. The images of the Lord and Lady seemed more real and it was as if they were really there in the circle. He heard their voices urging him to get up and fight after Ox had slammed him to the ground but had not been able to get back up.

Watching the initiations he saw them beside the candidates after they had given up fighting the six dark hooded figures. His parents kneeled beside the candidate as the circle began to move widdershins and the High Priest and High Priestess bestowed their blessings upon the initiate. Then it seemed as if they merged and flowed into the candidate and disappeared.

Later he asked Ellen about these things and she was interested in what he saw. Apparently he was able to see things even the High Priest and High Priestess had trouble seeing or feeling. More correctly he was seeing and hearing what a High Priest or High Priestess was supposed to be able to see and hear. She was excited about his natural talent and he spoke about some of the exercises and meditations that Crow and Llana had taught him. He didn’t mention his belief that the Lord and Lady were his parents.

There was no requirement for him to go to circle except during guard duty, but he always felt it was very important to show up and see how his Apprentice friends were doing and celebrate with them as they trained and soloed their own trainees. Fiona and Becca would be getting their sixth chevrons and he wouldn’t miss that. He was also looking forward to some quiet time with Becca.

He arrived just in time to change into his black robe and take part in the initiation ceremony as a guard. He didn’t have time to look for Becca or talk with any of his friends and none of them showed up during the day to chat. It was mid July and hot.

Becca and Fiona usually looked him up at least once during the day and he had a nagging feeling in the pit of his stomach that something was wrong.

He tried not to worry as he and Joy made sure the candidates were properly welcomed into the clan and later prepared for their initiation. This time he was the one that cut the gray robe and shortened it to become a tunic. He remembered his own Clansman initiation and felt satisfaction as he cut away the fabric of the tunic. It was the first time he had cut a tunic and it was kind of ragged in spots and high. He might have cut the tunic a little short but she was good looking and had nice legs. The shortened tunic looked good on her.

There were eight candidates and later the new clansmen were taken to the sweat lodge for purification and left to meditate. It was a long day and the eight initiations seemed to drag on forever.

After the last initiate was gone he headed toward the circle and noticed that both Fiona’s and Becca’s students had returned from their solos. They were hanging out by the beer barrel but he still didn’t see Fiona or Becca. He walked over to congratulate both of them on their solos and asked where the girls were. The look on both of their faces told him immediately that something was wrong. They were surprised he hadn’t heard. Yesterday rogues had attacked both Fiona and Becca. Becca had been raped and badly beaten. Medics had taken her to sanctuary. Fiona had gone with her to make sure she was all right. The kids had stayed behind.

There was a hollow sick feeling in his stomach and he felt like he was going to throw up. He was shaken to his very core by the news and his face turned a pasty gray. He looked for one of the medics to ask for more information and made a beeline in the dark to the nearest red cloaked figure he saw. The medic was busy putting some things in his pack. His back was to Tobal as he walked up.

“Excuse me,” He began. “I need some information.”

“ Rafe!” He shouted.

“Rafe, what about Becca?” He asked urgently. “Is she all right?”

Rafe turned a troubled gaze on him.

“Becca’s pretty bad. Near as we can figure four rogues jumped the two of them with clubs while they were climbing half way up the cliff on a ledge by the waterfall. Becca got taken by surprise at the top. They grabbed her and were holding her down and tearing her clothes off. She was fighting back when she was knocked unconscious. Fiona managed to slice one of them pretty bad with a blade before being pushed over the ledge. Becca was already unconscious when Fiona fell over the ledge. She wasn’t able to help Becca and prevent the beating. She’s lucky she wasn’t hurt in the fall.”

“Alarms went off on our air sleds and we responded immediately. The rogues left Becca with a couple cracked ribs and took off running when three medics came flying in on air sleds. Tobal, she was raped. ” He looked at Tobal before continuing.

“We felt she might have internal injuries and took her to the city for specialized medical attention. Fiona went along as a witness and to fill out the reports.”

That was all Rafe knew except they were both at sanctuary now and Becca was in stable condition.

“I don’t know who the rogues were. They don’t seem to be anyone that is a part of our camp. But they know about us, that’s for sure. They didn’t wear med-bracelets, so they didn’t show up on our screens.”

“They don’t wear med-bracelets?” Tobal said grimly. “That means they are General Grant’s men.”

“The air sleds showed up suddenly?” Tobal asked violently. “How did the rogues get away?”

“We don’t know yet. That’s our new camp remember.” Rafe continued. “As soon as Becca was knocked unconscious alarms went off on our air sleds. What I can’t believe is that rogues would be so close to our camp.”

“I know where they were climbing,” Tobal said suddenly. “If they were on the ledge they would have been trapped. The only way down was hand and foot holes and the only way up was through a rock chimney. They didn’t run away. The medics let them get away!”

Rafe turned white as understanding dawned. “It wasn’t our Medics. The rogues were teleported there and out again. They must have a teleporting station set up right there on that ledge. We’ve got to find it and destroy it.”

“What did these rogues look like? What kind of tunics did they wear?” Tobal asked savagely already knowing the answer. “They knew the girls were going to climb the cliff and waited for them on the ledge. The girls were deliberately ambushed!”

“’They were dressed as Journeymen in black tunics.” Rafe told him. “That’s all we know at this time. Ellen’s looking into it further and making a complaint to the City Council.”

There was a lump in his throat and a heavy feeling in his heart. He had left the girls at the lake alone and unprotected. Part of what happened to them was his fault. He had even suggested they go there in the first place. Tobal took up his pack and asked Rafe to give him a ride to sanctuary. The trip was a little over an hour with the air sled. The full moon made night travel fairly easy anyway. It was his first air sled ride but he was too emotional to enjoy it.

As they traveled he wondered about the rogues. Were they really acting under orders from General Grant or his Uncle Harry and did they have the ability to teleport in and out at will?

What was so important about the cave under the waterfall? They needed to really check it out before the enemy broke through the shield and took everything. He told Rafe that they needed to check the cave out thoroughly and see what they could find. Rafe agreed and said he and Ellen would look into it immediately on his return. He dropped Tobal off at sanctuary and sped back toward the lake.

Tobal went inside and stopped at the door to let his eyes adjust to the dim light. Fiona saw him and came running with a glad cry.

“Tobal!” She threw her arms around him in a big hug. “I’m so glad you’re here.”

She led him over to the cot where Becca lay and he sank down on his knees by her bed. He reached out for her hands. She smiled weakly at him. Her face was horribly bruised and there was a look in her eyes he didn’t recognize. He didn’t know for sure if she really knew who he was. It was like she was looking through him. As he reached to move a strand of hair away from her eyes she flinched away from him.

“Becca, it’s me Tobal!” He implored but her uncomprehending eyes remained the same. She was in shock. Part of her soul was gone somewhere else and he didn’t know how to get it back. He stayed with her and Fiona stayed with her but she remained unreachable. In anguish he grabbed her hand and placed it over the scars on his face.

“Becca, it’s me, remember me! My face. Feel the scars, it’s me, remember!”

She slowly looked at him and tears began to form in her eyes.

“Tobal.”

She softly traced the scars with her fingers. “I’m sorry.” She whispered and her arm dropped back on the cot.

He pulled her hand toward him gripping it hard and trying to bring her nearer. Something broke inside his heart and he cried, violent spasms shaking his body.

“Becca, I love you, I love you. Come back to me.”

Her fingers tightened in his. “I love you too,” she whispered.

Two days passed and Becca seemed to improve but something was still wrong. The rape and beating was still fresh and her experience made her both fearful and angry. She wanted to withdraw at times into her own space and be alone and at times she pushed both Fiona and Tobal away. Other times she needed them close to her.

It was the afternoon on the third day that Llana showed up at sanctuary concerned about what had happened. When Tobal hadn’t showed up for their meeting she had gotten worried and gone looking for him. She checked at the new medic’s base and was told that he was here.

“You’ve got to get Crow,” Tobal told her. “Crow told me that he would be needing to do another soul retrieval. He is the one that is meant to help her.”

“Both Crow and I will help her together,” She told him softly.

A few hours later both Crow and Llana had finished the soul retrieval and done spiritual healing work on Becca. She was sleeping peacefully. Crow, Llana, Fiona and he could not talk openly about things at sanctuary because newbies were there and clansmen were also showing up to get the newbies. Crow and Llana left and said they would talk with him later. Before they left Tobal warned them that the General’s men were teleporting into areas without warning and attacking clansmen.

They stayed at Sanctuary as Becca gradually improved. Both Becca and Fiona were looking forward to their Journeyman initiation and joked about it. The bad food at sanctuary was finally too much and they decided to make a leisurely journey to the caverns.

It had been two weeks and was just before the new moon. Physically Becca was pretty much healed but there were still deep emotional scars that were raw. He could feel the scars keeping them apart. Becca and Fiona were to be initiated into the Journeyman degree. They both felt it would help them to turn their minds away from what had happened. They traveled together and reached the caverns late in the afternoon. As the girls were being prepared for the initiations he joined the tail end of the tournaments.

Since he was late he hadn’t been challenged and was given the opportunity to challenge someone. He didn’t care whether he won or lost, he just needed an outlet for the rage and energy that had been trapped inside him since Becca’s accident. It was making him crazy and he knew he had to get rid of it.

In a burst of anger he challenged Ox. Ox had been having it entirely too easy because of his natural strength and size. Nobody ever challenged him and he only challenged weaker and easier victims. He never really had to fight. Tobal needed to fight.

Ox was surprised and incredulous but also had a wide grin on his face as he contemplated the beating he was going to give Tobal. Lumbering to his feet he swaggered into the circle and nodded at the referee. Tobal was on fire and there was no strategy. He was just going to pound Ox until the fight was over. It was going to be brutal but he was in much better shape and had learned a few tricks the past months. He had also been practicing daily. He had never seen Ox bother with any type of training or exercise. The brute seemed to rely exclusively on his own natural ability and strength.

Ox lunged and Tobal narrowly missed getting caught by those massive arms. As Ox passed Tobal swung a viscous blow with an elbow that caught Ox on the side of the head and dazed him. Tobal was not quick enough to take advantage and Ox turned with a bellow of anger. It turned into a slug fest in which neither one tried to get away but simply stood braced and pounded on each other, trading blows without regard for the punishment they were taking.

Tobal had learned how to brace himself for blows and took several blows to the midsection without buckling. Llana’s training had given him vast endurance and it was Ox who began to weaken under sustained blows to the head and midsection. He was used to fights that ended quickly and was getting tired. A wicked knee to the groin finally dropped Ox to his knees and the fight was over. Tobal was battered and bloody but victorious and happy. He had won his second fight.

There was something especially sweet about this fight he thought as he limped out of the circle. He watched as Jake fought his match. There was no doubt about Jake getting better too. But it was not enough for him to win.

As he left the ring and sat down at the edge of the circle his mind again returned to the conversation with Becca that had left his head spinning. He had asked Becca for a better description of her attackers. They had been bearded and hard to describe but she had torn the leader’s tunic off in the struggle. She had seen clearly a tattoo on his chest above his heart. It was a round circle with a male and female holding hands inside the circle. It was the same tattoo he had seen on his uncle as a child.

After the tournaments he washed up and got prepared for Becca’s and Fiona’s initiations. Having two initiations made things go much longer since they each had to be done separately. Becca’s initiation was first and it was almost the last. Tobal was Becca’s guide. He had requested to be her guide and Ellen had approved. He wanted to be close by in case something happened.

Posted in Uncategorized | Tagged books, fantasy, fiction, short-story, writing | Leave a Comment »

The Rebirth of Melchior Dronte by Paul Busson and translated by Joe E Bandel

I remained mute with amazement. It seemed to me as if I

were standing in front of an open gate, which I had carelessly

passed, without knowing that behind it was hidden the solution

to all questions.

“Understand me, brother. I’ll show you the way.”

“The wish at the moment of death –“, I said to myself.

“To take the consciousness beyond death — to save the memory

–“

“You have understood. Farewell!”

Slowly glittering in the twilight, his figure became

indistinct, only his face still shone.

“Stay, stay with me -” I wanted to call, but no sound

came out of my mouth.

Then he said slowly and clearly words, whose meaning I

no longer understood:

“Hamd olsun -tekrar görüschdüjümüze!”

I was awake, didn’t see him anymore.

“Isa bektschi!” I shouted. “Stay with me!”

But only my own hoarse voice echoed in the wide space.

Why had I understood him before and now I didn’t? And

it had been the same language – I remembered it as one

remembers a blown note whose tone, the sequence of which is

fading more and more from memory.

Hastily I spoke the unknown words to myself twice, three

times, until they were indelibly burned into my memory like

the words of a prayer recited a thousand times.

Why did my heart ache so much?

How many questions I still had to ask! How I would have

liked to ask him about Aglaja, about Zephyrine, about the

haunting of the night of hell.

Didn’t he say we were one?

“I am you?”

He was in me, and only from me could the answer come.

From the depths of consciousness, when the hidden would

awake. When the state occurred, in which all riddles spread out

legibly, like clear writing.

So calmly my heart beat, free from all fear, free from

expectation, and so safe and happy was I as a child in a

mother’s arms.

“Death, where is thy sting?”

Like distant, comforting ringing these words from the

holy book came to me. There was no death for the one who

wanted to live. Life for all eternity, life until complete